Canada 150 is a celebration of Indigenous genocide

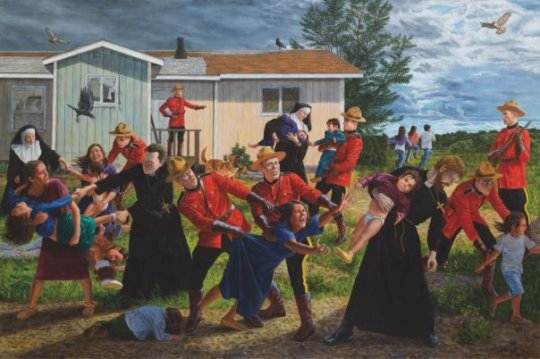

The Scream, on the cover, The Subjugation of Truth, by Kent Monkman.

by Pamela Palmater, Now Toronto, March 29, 2017

For many Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island (North

America), it’s difficult to imagine Prime Minister Justin Trudeau – who

has said that “no relationship is more important to Canada than the one

with Indigenous peoples”- celebrating the last 150 years of brutal

colonization and the foundation of what is now known as Canada.

This year, the federal government plans to spend half a billion

dollars on events marking Canada’s 150th anniversary. Meanwhile,

essential social services for First Nations people to alleviate

crisis-level socio-economic conditions go chronically underfunded. Not

only is Canada refusing to share the bounty of its own piracy; it’s

using that same bounty to celebrate its good fortune. Arguably, every

firework, hot dog and piece of birthday cake in Canada’s 150th

celebration will be paid for by the genocide of Indigenous peoples and

cultures.

Many places are struggling with the nation’s genocidal origins.

In Halifax, the school board voted to change the name of Cornwallis

Junior High because its namesake, Edward Cornwallis, was responsible for

putting bounties on the scalps of Mi’kmaw people, causing many deaths.

Likewise, in Toronto, Ryerson University has come under scrutiny for

its namesake, Egerton Ryerson, a strong supporter of residential

schools, where thousands of Indigenous children died violent, torturous

deaths.

Even the “Famous Five” women long celebrated as champions of women’s

rights have had their hero status questioned because of their support

for sterilization of Indigenous women. Celebrating genocide is not what

most would consider a modern Canadian value.

While use of the term “genocide” to describe Canada’s treatment of

Indigenous peoples has created a great deal of debate, there has always

been a recognition that, at minimum, Canada was guilty of “cultural

genocide,” even if individuals couldn’t bring themselves to accept more

sinister intentions.

Former prime minister Paul Martin told the Truth and Reconciliation

Commission (TRC) that it was time to call the residential schools policy

what it was: “cultural genocide.”

Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin weighed in

on Canada’s dismal human rights record, saying that residential schools

were attempts to commit “cultural genocide” against Indigenous peoples.

While these comments were made before the TRC report was tabled in

late 2015, they did raise questions in the public sphere about how to

recognize genocide when it’s not part of something like the Holocaust or

the war in Rwanda.

Despite the sensitive nature of making the claim of genocide, the TRC

went further after investigating the historical record, stating that

the totality of policies toward Indigenous peoples amounted to cultural,

biological and physical genocide.

The difficult part about public discourse related to genocide is that the majority of Canadians don’t have all the facts.

Most mistakenly believe genocide only occurs when millions of people

are killed in concentration camps. They’re not taught in school about

the real history of the atrocities committed against Indigenous peoples

that over time resulted in millions dying. Some universities teach

genocide studies without any mention of the lethal colonization process

in Canada.

The real history, however, shows that even after signing peace

treaties with First Nations, laws were enacted in Canada offering

bounties for scalps of Indigenous men, women and children. The treaty

negotiation process itself was conducted under conditions of starvation

or threats of violence. While some argue that these acts were committed

pre-Confederation, it must be kept in mind that they are in fact how

Canada became Canada.

“Indian policy” was based on acquiring Indigenous lands and resources

and reducing financial obligations to Indigenous peoples. The primary

methodology was either assimilation or elimination. These acts included

confining Indigenous peoples to tiny reserves and forbidding them to

hunt, fish or provide for their families, forcing them to live on

unhealthy and insufficient rations that caused ill health and

starvation.

It didn’t stop there. Other genocidal acts included the forced

sterilization of Indigenous women and little girls and the mass theft

from families of Indigenous children, many of whom were physically and

sexually assaulted, experimented on, tortured and starved at residential

schools – leading to the deaths of thousands.

This is how Canada cleared the land for farms, mining, oil extraction

and development. It simply would not be the wealthy country it is, one

of the best countries in the world to live and raise a family, were it

not for the removal of Indigenous peoples from the source of Canada’s

wealth.

The real crime, however, is not only Canada’s failure to take steps to right the wrongs of the past.

Today, more Indigenous children are taken from their families – now

put into foster care – than at the height of the residential schools

cruelty. The over-incarceration of Indigenous men, women and children

continues at alarming rates. Even though Indigenous people represent

only 4 per cent of the population, some prisons contain nearly 100 per

cent Indigenous inmates.

The federal government and law enforcement agencies have allowed the

crisis of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls to continue

with little intervention – suggesting complicity in the deaths.

The prime minister spoke at National Aboriginal Day ceremonies in

2016 about “the importance of reconciliation and the process of

truth-telling” in healing Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples.

He has no right to speak about reconciliation before he takes the

necessary steps to make amends. Canada has no right to ask any one of us

to talk about moving forward until the prime minister and all premiers

take responsibility for what their institutions have done – and continue

to do – to Indigenous peoples. No amount of token showcasing of

Indigenous art, songs or dances in Canada’s 150th celebration will stop

the intergenerational pain and suffering, suicides, police abuse,

sub-standard health care, housing and water, or the extinction of the

majority of Indigenous languages.

Perhaps Canada should humble itself, step back, cancel its plans and

undertake the hard work necessary to make amends for its legacy. Then we

could all celebrate the original treaty vision of mutual respect,

prosperity and protection envisioned by our ancestors. Until then, I’ll

pass on the cake.

Pamela Palmater is a Mi’kmaw citizen member of Eel River Bar

First Nation. She has been practising Indigenous law for 18 years and is

currently an associate professor and the Chair in Indigenous Governance

at Ryerson University.

How the United Nations defines genocide

According to the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and

Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, genocide is defined in Article II

as acts “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a

national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Described by the UN as

an “odious scourge” (repulsive evil causing great suffering), genocide

can be committed in any one of following ways: killing members of the

group; causing serious bodily or mental harm; inflicting conditions of

life meant to bring about their destruction; preventing births within

the groups; and/or forcibly transferring the children of the group to

another group.